OpenAI CLIP

Published:

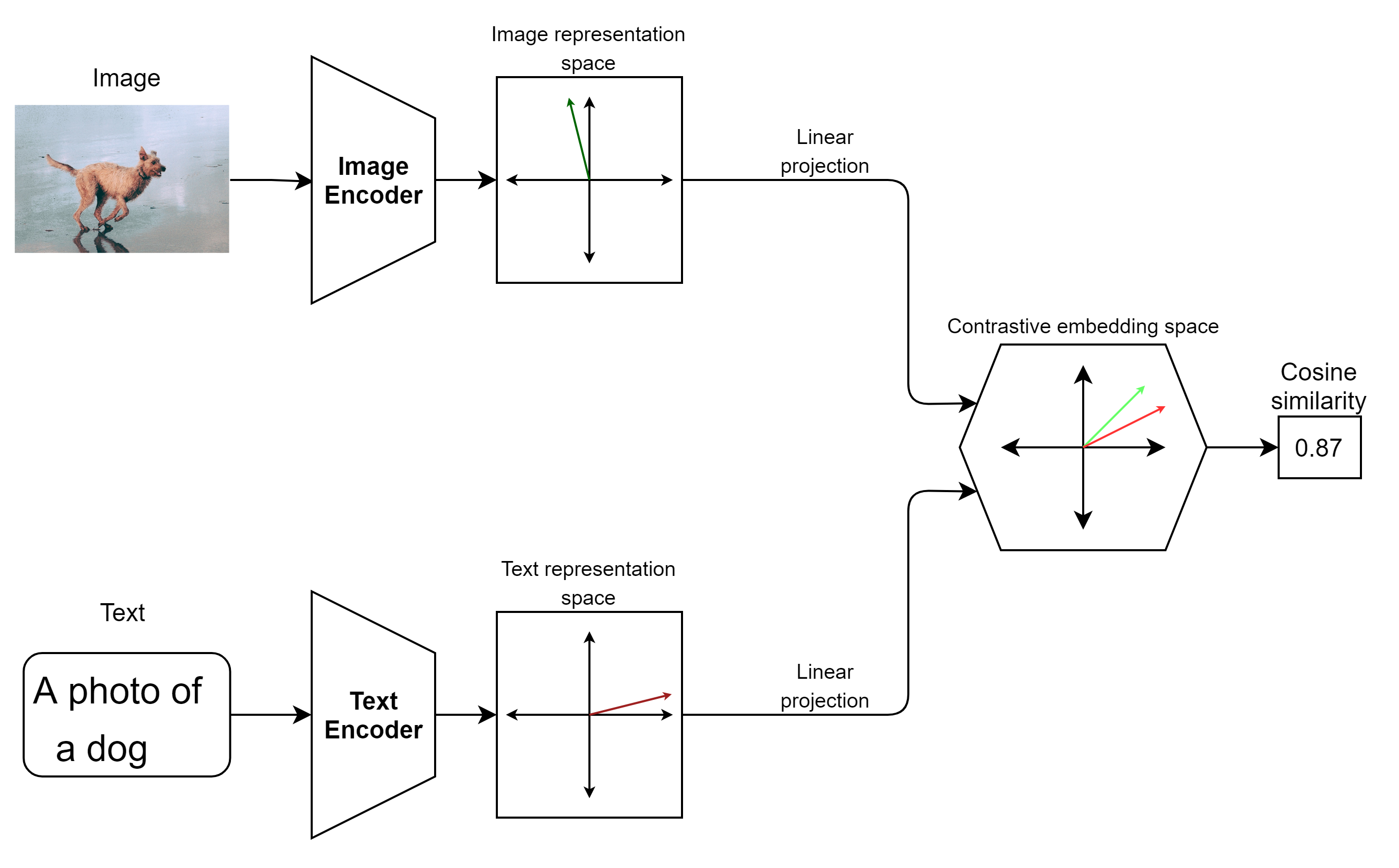

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) is a model released by OpenAI in early 2021 that jointly learns image and text representations. It has two primary components – a text encoder and an image encoder, and it works by giving similar outputs from these encoders when the input image and text are similar.

For example, if we input the image of a dog, the image encoder will output some encoded vector. If we now input text prompts like “dog” or “an image of a dog” or “the goodest pupper in the world” then the text encoder should give an output that is similar to the output from the image encoder.

In this post, I will try to summarise the key points about the model and its working based on the original blog post and the arXiv paper. The authors have also released the code on Github.

Motivation

Traditional image classifiers have several shortcomings that this model tries to overcome.

First of all, current vision models are usually trained on standard datasets like ImageNet, Open Image Dataset etc., and while these datasets do try to include a diverse set of images, it is very difficult to do so, especially in a static dataset. These datasets are good for benchmarking the performance of vision models but for training, they often do not provide the required diversity.

Second, a lot of presently available datasets are labeled by humans, which means the creation of new datasets is very expensive and time-consuming and limits how large these training datasets can get. Even when a large dataset is created, models are trained on them by trying to correctly classify the image from a fixed set of labels without making any attempts at understanding the meanings of the labels themselves. Naturally, when custom models are built using these large models as a pre-training step, these new models also inherit the same limitations.

By comparison, in NLP, large language modes like BERT and GPT-3 are trained in a self-supervised manner on very large datasets scraped from the web with very little human supervision. A GPT-3 like model would never have been possible with hand-labeled training data.

CLIP is a vision model trained using a similar self-supervised approach, which also allows it to “understand” the contents of an image better than traditional models as well as allows very good zero-shot performance on many common benchmarks.

Dataset

The dataset is made up of 400M (image, text) pairs scraped from the internet. To find these pairs, first, a set of about 500k queries were created using Wikipedia and WordNet. The exact process defined by the authors is as follows –

The base query list is all words occurring at least 100 times in the English version of Wikipedia. This is augmented with bi-grams with high pointwise mutual information as well as the names of all Wikipedia articles above a certain search volume. Finally all WordNet synsets not already in the query list are added.

The dataset is then created by searching these queries and pairing them with the caption found with the image. The resulting dataset is called the WebImageText (WIT) dataset.

Training

As mentioned above, the model has two primary components: an image encoder and a text encoder, and we want the model to learn that the images and their corresponding text labels go together.

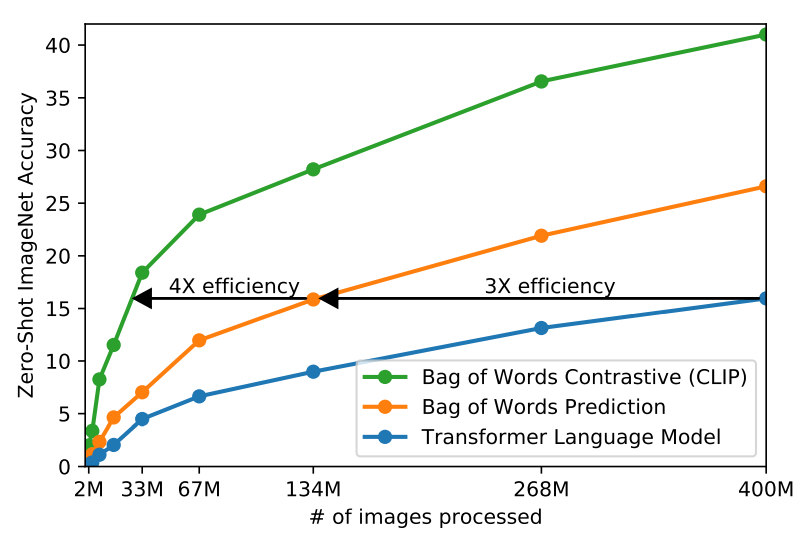

For the text encoder, the authors first tried transformers to predict the image captions, and found that they were very slow to train, and a simple baseline model that gives bag-of-words encodings as output learned 3x faster. The problem here is that both of these methods are trying to predict the exact caption paired with the image. The way the dataset is created, the captions do not follow any fixed guideline and, in general, are just a natural language description of the image. So, we know there is no ‘golden’ caption that is the most correct, and instead the same image can be described in many different ways that are all equally valid. What we really want the model to understand is that the caption paired with the image is one such valid description.

Contrastive learning

To achieve this, the authors used contrastive learning. Basically, we want to learn representations of data in such a way that inputs that are similar to each other are close to each other in the representation space, and inputs that are not similar are far apart. Using this approach, the authors found that the training efficiency became 4x higher than the bag-of-words baseline.

What this means is that CLIP is not a generative model, it cannot generate a caption based on an image, or vice-versa. Instead, given an image and a text prompt, it can tell how close they are to each other.

So the training task looks like this: given a batch of N (image, text) pairs, the model tries to predict the correct pairs out of all the possibilities. The text and image encoders are jointly trained using multi-class N-pair loss such that for the N correct pairs, the cosine similarities of the text and image embeddings are maximized and for the remaining N(N-1) pairs, the cosine similarities should be minimized. The loss function is defined as a symmetric cross-entropy loss over these cosine similarities.

There is a possibility that there are two or more (image, text) pairs in a batch where text from one example might be suitable for the image from another example, but given the wide range of classes (basically anything on public internet), the chances of that are pretty low so setting a target similarity of 0 for such cross-pairs should not impact performance. Also, given how large the dataset is, overfitting should not be a concern either.

To calculate the cosine similarities, the image encoder and text encoder outputs are both projected to a common contrastive embedding space. This is a simple linear projection as the authors didn’t observe any meaningful difference compared to using a non-linear projection.

Image and text encoders

For the image encoder, the authors looked at two choices and their variations –

- ResNet-50 – The authors make several changes including replacing the global average pooling layer with a transformer like multi-head attention-QKV layer.

- Vision Transformer (ViT) – This is a recent model that brings attention-based transformers from NLP to the domain of computer vision. The authors use the original architecture with the only change of using an additional layer-norm step on the embeddings before inputting to the transformer.

For the text encoder they used a Transformer with 63M paramters. The exact specifications are as follows -

As a base size we use a 63M-parameter 12-layer 512-wide model with 8 attention heads. The transformer operates on a lower-cased byte pair encoding (BPE) representation of the text with a 49,152 vocab size.

The authors experiment with various model sizes to calculate the effect on performance and compute requirements that you can find in the paper.

Zero-shot transfer

Given the way CLIP works, it can easily adapt to any classification task. We simply need to convert the labels into a phrase. For example, if we want to classify images from the CIFAR-10 dataset, where the classes are ‘bird’, ‘airplane’ etc., we can create prompts like “a photo of a bird” and so on. Then for any input image we can just calculate the similarities for all the possible classes, run softmax to convert the numbers into probabilities, and give prediction based on these probabilities.

Another way of looking at this process is that the image encoder is the underlying base model, and the text encoder acts as a hypernetwork. So, when we give a prompt to the text encoder, it converts the model into a classifier for that particular text.

In this way, we don’t have to do any fine-tuning on the target dataset and just the pre-trained model is able to give predictions – hence zero-shot transfer. Not only does this save time and effort in adapting the model to different use cases, but it also gives us confidence that the model is not tunnel-visioned on a specific type of data and is learning some general meaningful representations of the contents of an image.

Prompt engineering

The performance of the model on any task is highly dependent on the way the text is presented along with the images. In most datasets, the actual label of any class is not considered important since for training and validation a numerical class value is used and the models never even see these text labels. These labels are only used for human readability when reporting the results or showing examples.

This creates a problem for CLIP since it relies on these text labels to make its predictions. In the pre-training step, most captions are sentences of a few words describing the image, while the datasets used for benchmarking mostly have single word labels (“bird”, “dog”, “ship” etc. in case of CIFAR-10). The authors found that just using these single-word labels can hold back the performance of the model. In addition, only a single word without any context can often have multiple meanings – the word crane can mean a construction cane or a type of bird.

To mitigate these problems the authors turn these class labels into phrases like “A photo of a {label}”. While this general structure improves performance, it can be improved further by putting some more effort in prompt engineering and creating task specific prompts. I don’t know if classification after performing this step still counts as zero-shot but this is still much less effort than fine-tuning a large model.

Ensembling

Another way to improve performance is ensembling over multiple classifiers based on different ways to generate prompts. The authors give examples like “A photo of a big {label}” and “A photo of a small {label}” to show the kinds of prompts used in the process. Around 80 different prompts are used for ensembling.

Performance

Zero-shot performance

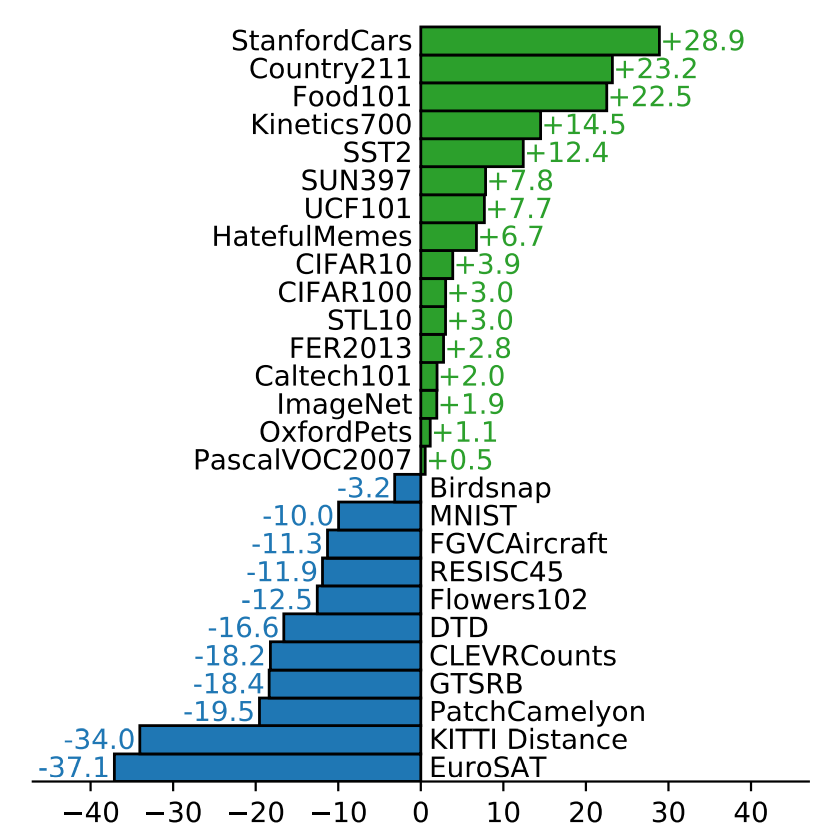

To get a reference for CLIP’s zero-shot performance on any dataset, the authors created a baseline model by taking the features from the ResNet-50 model and fitting a fully supervised logistic regression classifier on top of it, which results in a reasonably well-performing model.

As we can see in the results in the figure below, CLIP’s zero-shot performance is on par or better on most “regular” datasets like ImageNet, CIFAR10/CIFAR100, etc. while it underperforms the baseline quite a bit on datasets for specialized tasks like EuroSAT for satellite images and PatchCamelyon for lymph node tumor detection.

This makes sense considering the way the model is trained and the dataset. Images found on the internet probably do not include a lot of examples of how to spot a tumor in lymph node tissue or how annual cropland differs from permanent cropland. So we can see that while CLIP shows impressive zero-shot performance, just like humans it would also require some special training to be able to do specialized tasks well.

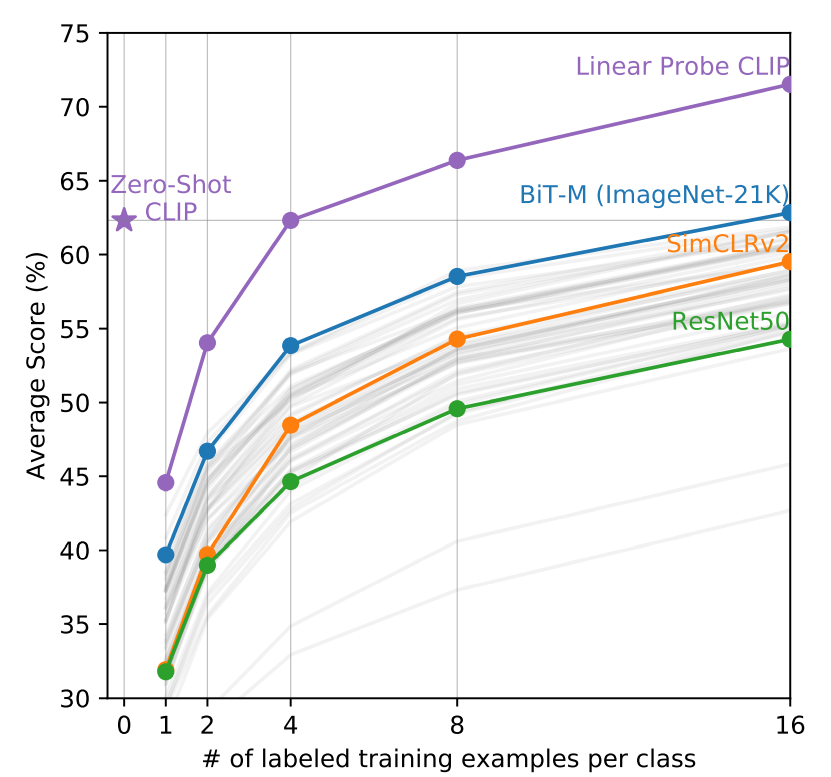

Few-shot performance

Let’s now look at how well CLIP performs if we give it a few examples of the task. To make the comparison fair, we will also use few-shot linear probes on large pre-trained models for comparison. The linear probes are created by taking large pre-trained models and replacing their final classification layer with a linear classifier that is trained on a few examples. This is different from fine-tuning the models since we are keeping the base model fixed and only using the examples to set the weights of our probe.

When we do this operation on the CLIP model, we make a significant change going from zero-shot to one-shot. In the zero-shot setting i.e. the regular CLIP model, the labels are provided in the form of natural language prompts that are encoded by the text encoder, which effectively turns the rest of the model into a specialized classifier for that particular task. In the few-shot approach, we don’t use the natural language prompt so while the model gains some information about the task by the examples, it also loses its ability to understand the image’s natural language caption. The result is that the one-shot performance of CLIP is actually worse than zero-shot and it takes about 4 examples to offset the disadvantage of losing the information from the text prompts.

We can see that the 4-shot linear probe on CLIP matches zero-shot performance and above that, performance keeps getting better. So it might be a good exercise to try and find a better way of making a few-shot version of CLIP that can keep the best of both worlds.

Conclusion

CLIP is a very interesting way of training vision models. The basic idea of learning text and image representations together for understanding image content using natural language feels very intuitive, and after seeing how well it performs on many tasks it wasn’t explicitly trained for, it seems surprising that many other models haven’t done so before. CLIP can be used as an image classifier given multiple captions or as a text classifier using multiple images as options, and personally I would really like to see this approach developed further for pre-training large vision models.

Leave a Comment